|

|

|

|

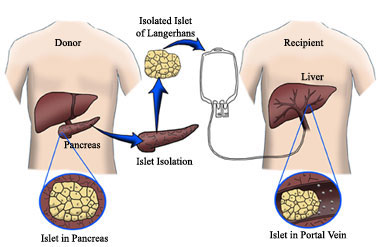

In islet transplantation, islets from a deceased donor are infused (dripped) into a vein in the liver. (See Procedure.) If the transplant is successful, the islets lodge in the liver and start to produce insulin. While islet transplantation has generated considerable interest, it's still considered an experimental procedure and is not an approved treatment. Rationale for Islet TransplantationInsulin therapy, given by injection or insulin pump, is life-saving. However, it's not perfect. Most people with type 1 diabetes still have blood glucose levels that are above normal. This puts them at risk for the long-term complications of diabetes. Those who are able to keep their blood glucose levels near normal often have trouble with low blood glucose (hypoglycemia). And after many years, some people lose the early symptoms that warn them that their blood glucose level is dropping. This is called hypoglycemia unawareness and raises the risk of severe hypoglycemia. Some people have what doctors call labile, or brittle, diabetes. Blood glucose levels swing from high to low despite the best insulin plans. The potential advantage of islet transplantation over administration of insulin by injection is that the transplanted islets would maintain normal blood sugar under all conditions, and would not produce excess insulin resulting in hypoglycemia.

The CIT Consortium is conducting studies to find methods that have higher success rates and fewer risks. History of Islet TransplantationThe concept of islet transplantation is not new. English surgeon Charles Pybus (1882-1975) tried to graft pancreatic tissue to cure diabetes. Most credit the recent era of islet transplantation research to Paul Lacy's studies dating back more than 3 decades. The first human trials were done in the mid-1980s. By the late 1990s, methods had gotten better. But still, only 8 percent of recipients were free of the need for insulin therapy 1 year later. In 2000, Dr. James Shapiro and his colleagues at the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, Canada, published a report describing seven consecutive participants who didn't need insulin injections for at least 4 months following one, two, or three islet transplantations. The transplants were done with a new protocol, using steroid-free immunosuppression and large numbers of donor islets. This Edmonton protocol has been adapted by islet transplant centers around the world and has greatly increased islet transplant success. The PresentThe goal of islet transplantation is to maintain normal blood sugar levels without the need risks of hypoglycemia. Short-term findings from various islet transplant programs across North America have shown that:

Rates of insulin independence for all three groups were lower at one year, but for those who received one and two infusions, rates were above 50%. One review showed that of 37 participants at three centers, 28 (76%) were still off insulin at 1 year. A study published in 2004 reported that of 11 islet recipients, 56% were still insulin-free at 1 year. Recently, the results of a follow-up study of 65 participants receiving islet transplantation in Edmonton, Canada, were published.

|

| Home | |

|